What Is It

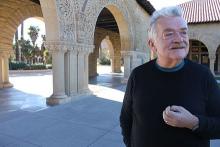

In the 18th and 19th Century, philosophers and intellectuals were immersed in politics and popular culture. Even in the early 20th Century some of the leading academic figures of the time, like Betrand Russell, also wrote for a broader public. Where have the public philosophers and public intellectuals gone? Can philosophers and intellectuals still speak to a broad public? If they speak will the public listen? Or is the public intellectual a thing of the past? John and Ken contemplate the place of the public intellectual in the modern world with Hans Gumbrecht, author of Reading Moods: On Literature's Different Reality. This program was recorded in front of a live audience at the Marsh theatre in San Francisco

Listening Notes

Ken and John first confront their guest with the question of why philosophers have receded from the public realm. Hans asserts that philosophy has become too much of an academic discipline. In the 18th century, 'philosopher' signified what we would now call a public intellectual. Today, that title merely refers to one's occupational affiliation with a university department. Ken challenges the idea that the field is too technical. Hans continues that the field is still too rational, and that the other problem is a lacking public awareness that philosophy is not just for students. In his opinion, philosophy needs to get ‘weirder’ to be more provocative.

In the next segment, Ken and John compare philosophy to other humanities and the sciences. While philosophy isn’t experiencing an identity crisis like in comparative literature, Hans’s department, it doesn’t carry the same social importance as science. Imagine the public’s reaction if the scientific community disappeared, Ken remarks. How do we bring philosophy back? Hans believes philosophy can answer the current need to reinvent our society. Philosophers shouldn’t only be appointed as specialists for the government’s reference, but should be bringing their own weird proposals forward. He mentions Peter Sloterdijk, who gained a lot of attention in Germany for his newspaper article challenging the idea of paying taxes. John supports this with the American example of Ayn Rand, a similarly influential philosopher. However, Hans clarifies that the purpose of philosophy is not to provide an ultimate orientation, but to begin discussion. Ken agrees, saying philosophy’s power is in the realm of imagination: it doesn’t tell us how things are, as with the sciences, but how things could be.

Ken, John, and Hans then explore how to change the current attitude. Hans believes the problem is in how philosophy is taught—or rather, the fact that it is taught. He thinks there needs to less instructing and more doing through contemplation, by getting students to focus on a text in depth. Ken agrees but is skeptical that such a method will have retention in an American society obsessed with payoff and measurable results. He asks Hans how he addresses this with his students. Hans jokes that he gives them all A’s. He closes the show on this idea of philosophical contemplation as the secular form of what is attempted in spiritual exercise.

- Roving Philosopher Report (Seek to 6:01): Caitlin Esch talks to Mike Lee about his volunteering efforts to introduce philosophy to children in LA public schools. They examine whether making philosophical discussion a habit from a young age can address the lacking ability of adults to articulate coherent moral positions.

- 60-second Philosopher (Seek to 49:00): Ian Shoales discusses the ‘Great Books’ phenomenon, and how widespread American enthusiasm to engage with influential texts of Western society suffered under the real practical and ethical implications of such a collection.