Trust and Mistrust

Dec 29, 2013If we couldn't trust each other, our lives would be very different. We trust strangers not to harm us, we trust our friends to take car...

One of the ideas I’ve seen cropping up on social media and in media punditry (especially since 2016) is that polls are untrustworthy. The thinking goes like this: the polls predicted that Hillary Clinton would win; she didn’t; so polls must be useless (or at least no longer useful) when it comes to making political predictions.

Such skepticism about polls is sometimes expressed in a sincere way, but often it is also expressed in a sneering way, as if to say: “You fool! You use polling data. Ha!” The general idea is that we live in an age in which people are so cynical that people’s answers to pollsters no longer reflect how they’re likely to vote.

Such thinking is worth addressing head on. It seems to me to be part of a broader assault on objective, systematic research that has also been on the rise since 2016. That assault—insofar as it undermines trust in real journalism and research—paves the way for propaganda, conspiracy theories, and other politically pernicious narratives, which thrive in ignorance. So the assault should be countered as much as possible.

My general stance, which is fairly standard among people who think at all seriously about polls, is that they are useful information sources under certain conditions. What are those conditions?

Does the election of 2016 undermine that stance?

No, it doesn’t. The claim that it does rests failing to respect condition 3). Hillary Clinton was leading in national poll averages by about 2-4% on the eve of the election. So the fact that she lost the electoral college does not show that the national polls were useless. All it shows is something we knew all along: one can win the popular vote without winning the electoral college. If we respect condition 3) and use the national polls for the question for which they were intended (who will win the popular vote?), we see that they predicted things fairly well: Clinton received 48.5% of the popular vote; Trump received 46.4%. So national polls predicted what they were supposed to predict, namely, the popular vote. (It is fair to say, I grant, that national polling on the whole underestimated support for Trump by a percentage point or two, but that’s a far cry from implying polls are useless; it just means they may benefit from some tweaking.)

But what about predictions from state polls that were supposed to tell us about the electoral college? Didn’t they get it wrong?

In this case, the answer is: “sort of, but not really.” Through the election season, the well-known polling and statistical modeling website 538 posted a continuously updated probabilistic prediction of the 2016 election outcome that integrated all state-level polls. 538 was and is considered a gold standard in the use of statistical modeling to make predictions about everything from politics to sports. And what were the odds they assigned Clinton and Trump on the eve of the election? They had a 71.4% chance of Clinton winning and a 28.6% chance of Trump winning.

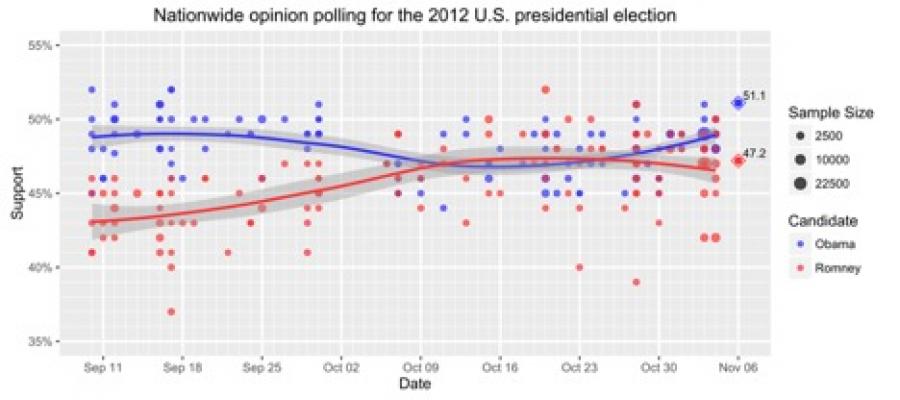

The first thing to note is that this indicates a high level of uncertainty. They gave Trump close to a one in three chance. So given their model based on state polls, Trump’s winning was regarded as about as likely as rolling a 2 or 4 on a single six-sided dice. Otherwise put, Trump’s win might have been surprising to most, but it actually wasn’t surprising to anyone who had a clear view of the polls: the outcome was uncertain, and Trump had a non-trivial chance of winning. (By way of contrast, similar modeling gave Obama over a 90% chance of winning on the eve of the election in 2012.)

Furthermore, shortly before the election, 538 was extremely clear that Trump had better chances in the electoral college than he did in the general. And that judgment was based on state-level polling data. Just consider a couple quotes from this prescient article from November 1, 2016: “In fact, Clinton would probably lose the electoral college in the event of a very close national popular vote.” “If the results are tight next Tuesday…Michigan and Wisconsin are much more likely to swing the election.” Sound familiar?

Given all that, it’s clear that the polls in 2016 were still useful, as long as you used the right ones for the right questions and grant that there was a high level of uncertainty. One way polls can get things right is by telling you to be uncertain when things really are unpredictable.

So if you like using polls to keep your finger on the pulse of the electorate, you should go right ahead, as long as you use them in a balanced way. If you do this, you will be far better off than most pundits (public or private) who ignore the polls and instead have “theories” or “intuitions” about what’s going to happen. And you will also be far better off than you would be if you just relied on your own “theories” or “intuition.”

The importance of this point, as I suggest above, is that a healthy awareness of polls can help combat propaganda and misinformation. That’s true in part because awareness of any politically relevant objective information can combat those things.

But there’s also a specific narrative that’s worth combatting at this time, and polls in particular can help do it. Many have said—and continue to say—that Trump will win again, and there is often a tone of certainty to such predictions. So it’s easy to fall into doom and gloom thinking. And if you believe those who dismiss polls, then the polls won’t be an antidote to the doom and gloom. But we just saw that dismissing polls is based on sloppy thinking.

So what do the polls currently say?

Right now, the latest polls have Biden, Bernie, and Warren each leading Trump by 9-11% nationally. Furthermore, about 52% of people polled say they will vote “definitely against Trump.” Of course, it’s early days, so it would be foolish to conclude that Trump won’t be re-elected…and there is always the dismal prospect of another popular vote / electoral college split. At the same time, a healthy view tells us that he is extremely vulnerable at best, which contradicts the misinformed narrative that confidently predicts his win.

Furthermore, for anyone voting in the democratic primaries, we needn’t be anxious about compromising quality for “electability”—all the front runners have a great shot at beating Trump.

So all in all, it turns out to be a good thing that polls are more trustworthy than many public pundits or social media trolls would claim. And the fact that they’re trustworthy is good, because lately they’ve been bringing good news.