What Is It

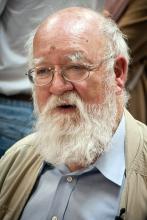

We like to think of ourselves as rational agents who exercise conscious control over most of our actions and decisions. Yet in recent years, neuroscientists have claimed to prove that free will is simply an illusion, that our brains decide for us before our conscious minds even become aware. But what kind of evidence do these scientists rely on to support their sweeping conclusions? Is the "free will" they talk about the same kind of free will that philosophers have puzzled about for millennia? And could science ever prove that we lack the kind of freedom needed for moral responsibility? John and Ken free their minds with Daniel Dennett from Tufts University, author of Freedom Evolves and Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. This program was recorded live at the 19th annual Undergraduate Philosophy Conference at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon.

Listening Notes

Can neuroscience answer the question of whether we have free will? Or is this issue best left to philosophy? John and Ken attempt to pin down what role, or lack thereof, neuroscience has in the discussion of freewill. Ken finds neuroscience to be extremely relevant, providing us with numerous experiments that appear to show the brain, and not our conscious selves, as behind our decisions. John considers this ridiculous, claiming that such evidence is completely irrelevant to the question, claiming that we already know our decisions are subject to causation, and it poses no threat to the concept of free will.

Our hosts are joined by Daniel Dennett, philosophy professor at Tufts University, to help them sift through what is important and what is not when it comes answering questions around free will. Ken argues that neuroscientists are guilty of taking the "man on the street's" definition of free will, resulting in their misunderstanding of the topic altogether. However, Ken defends this definition, claiming that it is the notion of free will that most people hold - the "philosopher's" definition is what's irrelevant. Daniel distinguishes between two different features of the layman's definition of free will, and argues that only one of them is truly important.

Members of the live audience are asked to join in on the discussion and contribute questions. One audience member questions whether we can have free will at some times and not during others, to which Daniel responds sympathetically. We are quite familiar with situations like obsessions and cravings in which we feel our will being influenced. Rather than causation, however, what Daniel refers to as most important to him in the entire discussion of free will is the notion of moral competence. The show ends with our hosts agreeing somewhat more thabn

Roving Philosophical Reporter (seek to 7:12): Shuka Kalantari investigates the science of magic to see how our decisions can be influenced without us noticing.

60-Second Philosopher (Seek to 45:43): Ian Shoales explains his confusion with the idea of free will.

Comments (1)

Harold G. Neuman

Tuesday, January 25, 2022 -- 2:11 PM

Had to go back a few yearsHad to go back a few years into your recent shows to find this, first aired in 2015. I have thought about will and have read some of what Schopenhauer wrote about it. Over another few years, there has been much discussion of free will. Some claim we have none. Others say we do. To still others, the difference is moot: there is just no sense in spending time and skull sweat on the matter. It has taken several years of meditative deliberation and a pandemic for me to deduce that it does matter. Will is something we must exercise to overcome adversity and graciously accept goodness. Free will is an exercise of choice, when, of course, there is such. In that limited sense, we have no free will---when there are choices, we do. The elements are unkind right now-a January to forget. I could have remained indoors this morning, instead of scraping snow and ice and taking my chances on the road.

But, I like the coffee at a nearby gasoline and convenience store. And at six a.m., there are fewer people out anyway.

So I chose to go for the coffee. The choice was freely made, albeit on the basis of experience. Aha, says the naysayer: you had no freedom of choice in the matter because a favorable expectation had predetermined your action. Partly true, yes. However, I could have as easily flipped a coin and allowed that outcome to guide my intention: the coin-toss would have also been freely chosen; the outcome, predetermined. My choice. My actions. My responsibility. After some length of time and due deliberation, I decided to compose and submit these comments, on a topic that does not bother me much. I suppose the megalog on free will be continuing into a distant future. It is one of those pithy topics which have occupied philosophy with ire and irony for ages. A conundrum perhaps. Or maybe just a prisoners' dilemma...